How in the name of Godot are we going to get fluent in French?

Richard’s about to return for his fall session at L’Alliance Francaise, and is not at all pleased with his progress to date. He's still in what he describes as the first-person pointing and grunting stage, although his pointing and grunting accent is superb.

I’m trying a different approach. Either an hour (minimum) a day of conversation in French, or an hour (minimum) of French film or TV show. You think getting into a French conversation is so easy? All the natives want to practice their English on me—English that is already fluent—but I bat them down, pretend not to understand English, or tell them they can practice their English on Americans who don’t want to learn French.

I’ve taken French classes, in high school. Madame Martineau was good for the grammar, good for the accent.

I’ve tried learning French online. Forget it. E-mail and Facebook, not to mention writing, are plenty on the small screen.

A film or TV drama—that’s my favorite way. Because nothing is better than a story. Some things are as good, but nothing is better.

Next is news. If you watch for an hour, the same news repeats, and you can scoop up new words when the same stories loop around again.

And sometimes an educational program gives you intensive familiarity with the vocabulary of one realm, food, for instance. The other night I watched a French journalist go from one location to another in Switzerland, interviewing food producers. She began on a farm high in the Alps, then swooped down to a chocolate factory in Zurich.

She was a perfect interviewer/hostess, friendly and subtly attuned to each person she interviewed, not so beautiful that she intimidated her interviewees, but a comely companion for bopping all over from valley to mountain and city to lake.

She spoke to a cheese maker and his family high on a mountain farm, to a bonneted chocolate maker, to a fisherman on Lac Leman, to a cherry grower (the dark are the best), to a German-speaking sausage maker who included the cherry grower’s cherries in his sausages, to the head of a finishing school where women from around the world learned to set a table à la Francaise and à l’Anglais. (To do it à la Francaise you put the wine glass smack in the center above the head of the plate-- metaphor for the reign of the grape in France?) The women were taught how to measure equidistant between the plates and line them up precisely the same distance from the edge of the table. The kind of thing you don’t learn as a young maenad in Berkeley.

Then there was the Frenchman who looked like a much taller Roman Polanski. He took the journalist on a river cruise, and talked eloquently about the smells of plants along the river in that sensual French way (she seemed smitten), then they disembarked, hopped on his Harley and roared up to his hillside restaurant where he cooked up something tasty for her. I know it was tasty from the sounds she was making, though I’m not sure what it was—I was distracted by the chemistry between the two of them. The moral of the story? You can look like a rat but if you’re humming that sensual tune, who cares, there’s magic in the air.

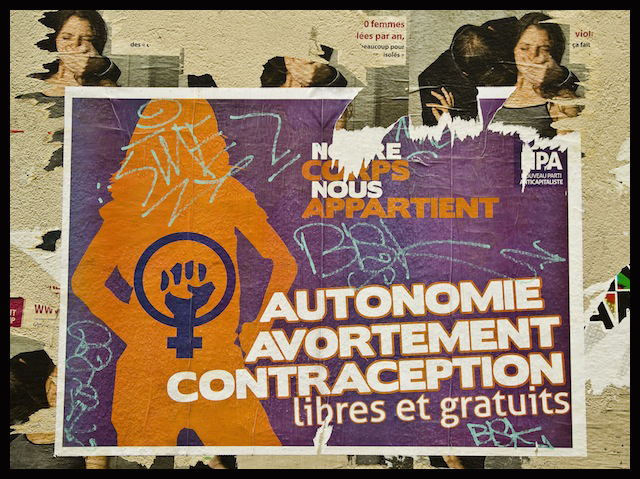

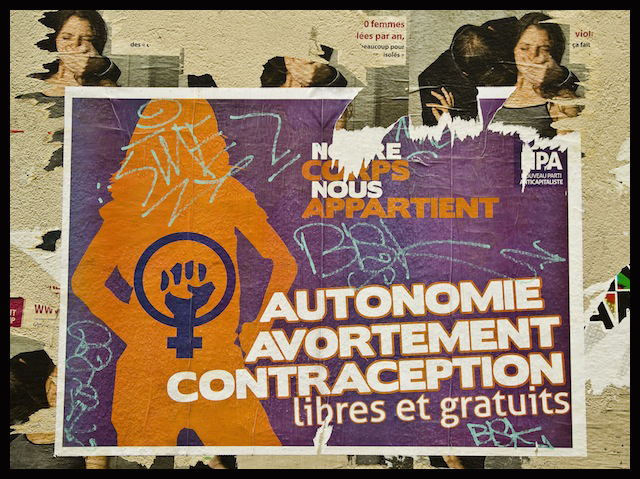

Then there was the two-hour history of feminism in France, from the ‘60s ‘til today. You think that women really haven’t come very far? Think again. This was an eye-opener. From the early image of a Frenchman opening a girlie magazine in the mid-‘60s (“Oh la vache! Oh, la pute!) to the ‘70s, which seems to have been the wake up call for Frenchwomen, when it seemed that every prominent Frenchwoman in the country signed a document insisting that women, and only women, should have a say in whether they have the right to choose an abortion.

Every Frenchwoman whose name you’ve ever heard from that era was interviewed in period footage, and spoke out with great dignity and conviction—and charm! Jeanne Moreau, Brigitte Bardot, Juliette Greco, Simone de Beauvoir, and many more.

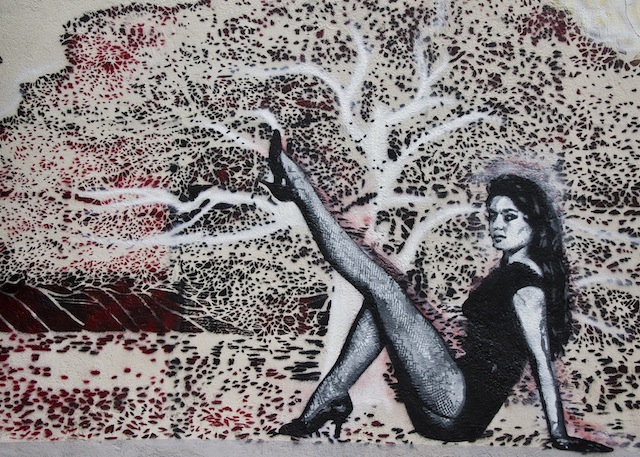

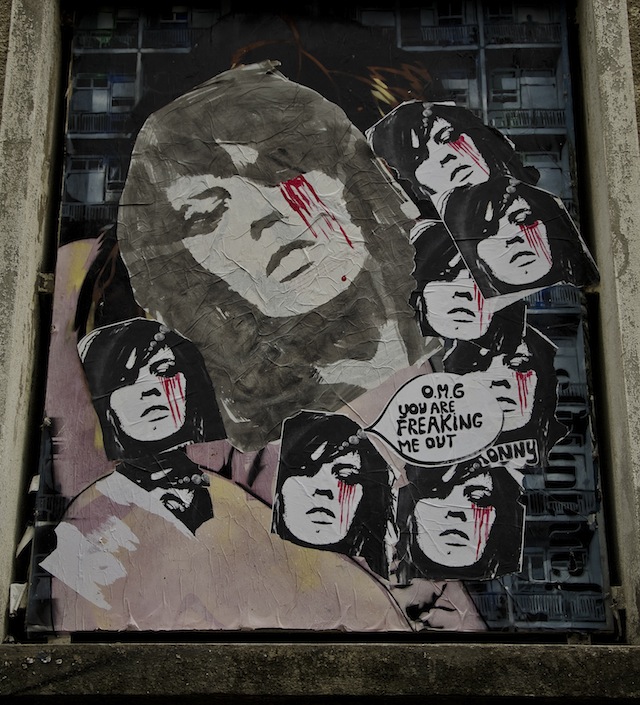

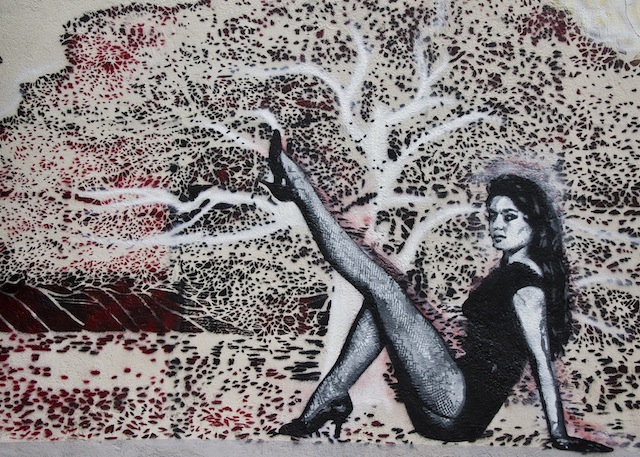

Bardot by Jef Aerosol

Bardot by Jef Aerosol

Men were interviewed on the streets as well. The humorless, straight-jacketed types all said women should stay at home, they don’t belong in the workplace. The men you’d want to know, the ones with juice in them said, Why not, if they want to work?

(To control or not to control, that is the question. Which brings to mind that late medieval English story, Sir Gawain and the Lady Ragnell, about what women really want.

Those Celtic storytellers knew the answer to Freud’s question centuries before he posed it.)

Slowly, women are shown entering government. Slowly, women are hired as news anchors. A few here and there, including a smart, sassy, dimpled, smiling young Anne Sinclair, now Dominique Strauss-Kahn’s wife. (You know, the one who gave the NYC hotel maid such a gracious thank-you tip?)

And then, a woman anchoring nearly every TV news hour, and then… two evening anchors, both women.

**

And lastly, to get my daily French language dose, I’ve descended to watching an occasional reality show, a level to which I was never tempted in the U.S. Okay, maybe this is a concept that has already been embraced in the U.S., too, but I doubt it. I watched a show called “Belle Toute Nue.”

Here’s the basic theme: a woman with a zaftig figure comes on the show ready for transformation. To lose weight? you ask.

Mais non!

To become “bien dans sa peau,” to fully embrace herself as she is.

Her transformative wizard is a delightful, stylish, warmhearted guy named William. If he isn’t gay, he’s a terrific actor. And if he weren’t gay, I doubt that a single woman would allow him to take the liberties he takes with them.

There is a formula here. I know because I’ve watched the show twice. A woman arrives at William’s dressing room studio. He has a heart-to-heart with her about her body image. She cries.

One was a 19-year-old blonde who’d gained 30 pounds in three months because of an illness, and kept gaining. Another is a woman in her early 40s who won’t let her husband get physically close to her.

The stages:

Stage one: Confession.

William gently, lovingly asks the woman about her body image. She weeps. He asks her questions. She answers. He asks her to strip down to panties and bra and stand in front of a big three-way mirror. She is to go down her body, feature by feature, describing how she feels about each part.

Here. And here. She points to her thighs, her stomach. Again, she weeps.

But one of the women has to concede that she likes her eyes.

And the other likes her calves, sort of.

Stage Two: Lineup/Cattle Call

William leads the blindfolded woman into a room where five buxom abundant-bodied women in fetching lingerie (lined up according to size) are dancing to festive music. When they stop, the woman is asked to “take her place” according to size. Is she bigger than this one? Smaller than that one? She has no idea. She chooses a spot, slides in between two women.

No, says William. That is not your place. Try again.

She studies the women, fascinated. Again, she picks the wrong spot between two even larger women.

At last William shows her that, actually, she is the smallest of these women. And they’re all beauties. So perhaps (she thinks) she’s not all that big, that bad.

Stage three:

This is the part I can’t imagine seeing on an American “reality” TV show. But maybe I’m wrong. Readers, you tell me.

One day, as the woman walks through Paris, wearing camouflage clothes well chosen to hide her body, she bumps—serendipitously!—into William. To the young woman who works in a farmers’ market, he says, I was just on my way to shop for veggies—maybe you’d come along and give me some shopping tips?

They chat among the vegetables, and suddenly her hand flies up to her mouth. She has spotted the photo card among the eggplants—a photo of her wearing nothing but panties and a bra! Oh my God! she exclaims. And then—another photo! And another! In every vegetable bin, there is a big photo of her nearly naked body. And at the end of the market: Oh no! A giant poster of her, the same image.

William stops passersby to point at the poster and ask what they think of this woman.

Jolie. Sympa. Belle poitrine. Etc.

She listens while young and old, male and female appraise her, and mostly praise her.

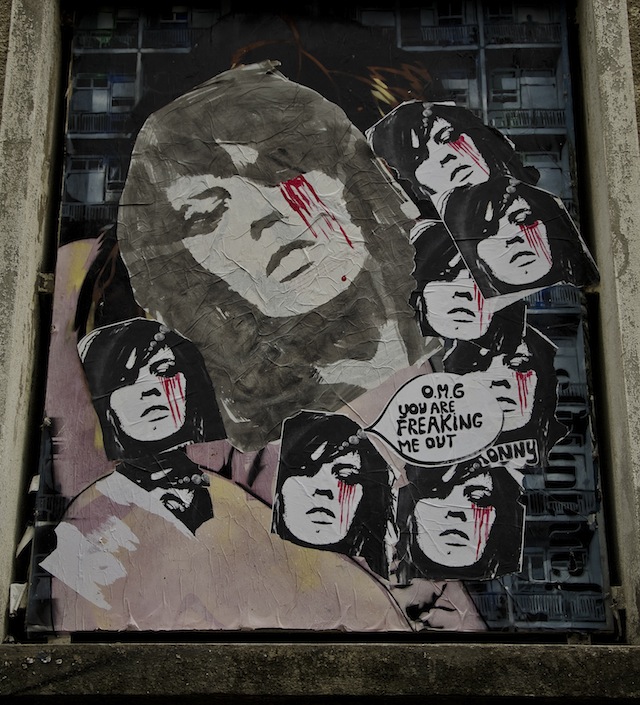

Hairspray

Hairspray

Stage four:

A clothes shopping trip, of course. William is the personal shopper of most women’s dreams. In ten minutes flat, he’s discovered her favorite colors, and whipped off the racks dresses, a trench coat, blouses, jeans, beautiful shoes, belts. And lingerie. French lingerie. A fitter comes to get that bra just right.

Do clothes make the man? I don’t know, but they THRILL the woman. Dessert is a many-petalled long red silk strapless dress (it looks like a Valentino) that is smashing, and she looks smashing in it.

Stage five:

Hair and makeup, Parisian stylists and makeup artist. One woman goes from a hairdo that looks like a limp brown mouse died on her head to electric white-blonde Sharon Stone short. Transformed!

Another from nondescript blondie to blonde China doll, straight bangs, long bob. Dazzling.

Stage six:

The show. The climax. The reveal.

Knowing that the 19-year-old is mesmerized by the Folies Bergère dancers, William takes her to the Folies Bergère, where she is trained by their choreographer and taken on stage looking like a Seventeen magazine cover girl movie star showgirl, and—husband and friends in the theater audience—does a strip tease fan dance with the Folies Bergère dancers cavorting around her.

The married 40-something-year-old poses nude (tastefully) with her Sharon Stone hair and new violet glasses for a photo session, and stage show for her husband and family and friends on a revolving stage with other zaftig women flanking her.

The show succeeds in giving these women the feeling of being “bien dans sa peau,” which is the very thing that is so striking about Parisian women. It’s really a question of attitude, isn’t it? Just watch her walk down the street.

It also succeeded in teaching me some essential new French phrases like:

Il veut aider les femmes se débarrasser des complexes. (He wants to help women get rid of complexes.)

Vous ne sauriez croire combien un bon saucisson se marie avec quelques cerises. (You wouldn’t believe how good sausage and cherries are together.)

**

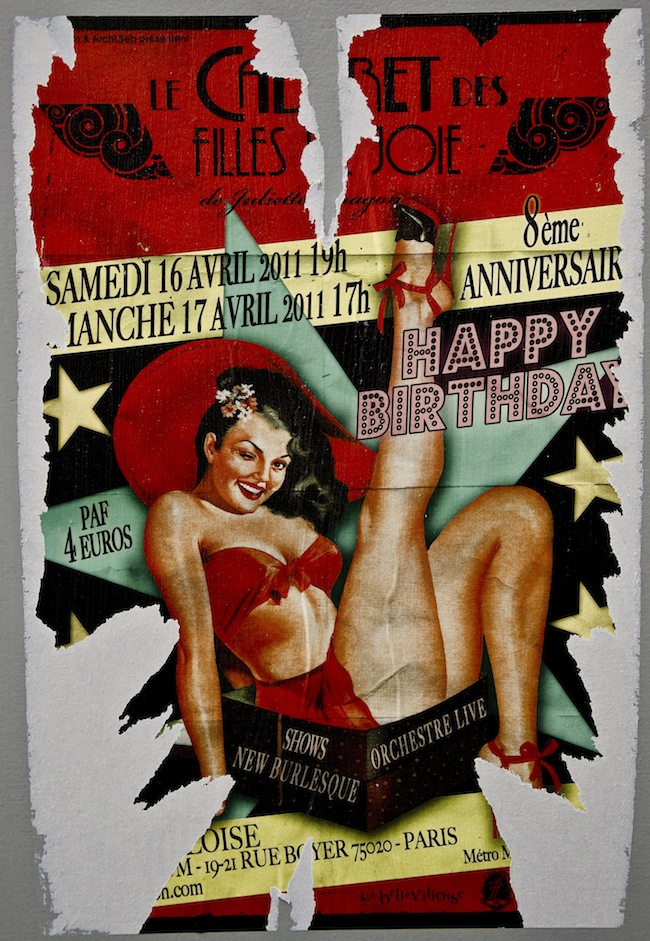

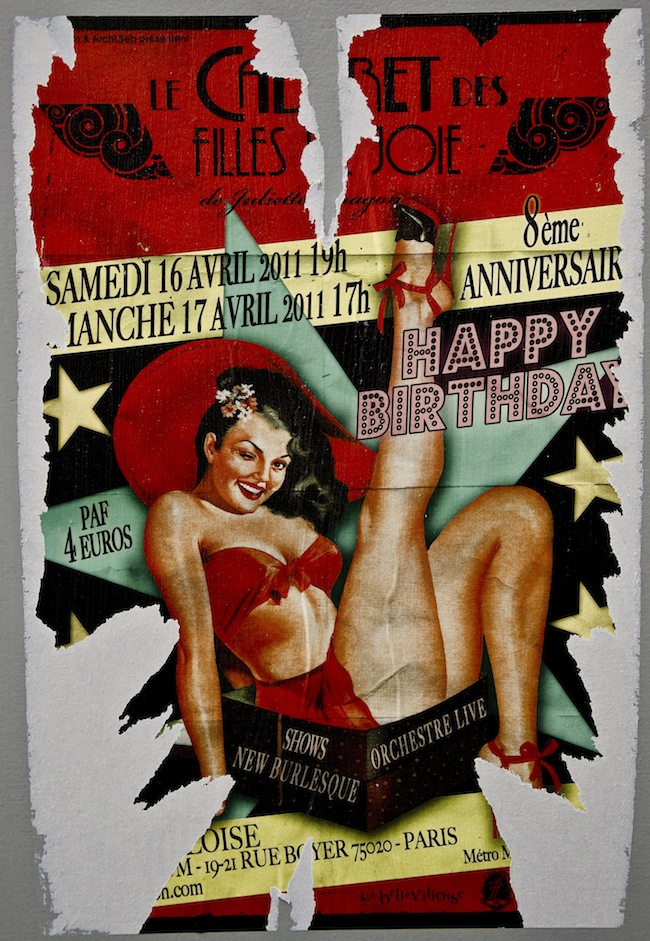

P.S. I can’t believe we missed this event right at the end of our street.

08.11.2012

08.11.2012

I'm having a cappuccino at a local cafe, and she just walks up and sticks her face in the lens. How could I say no?

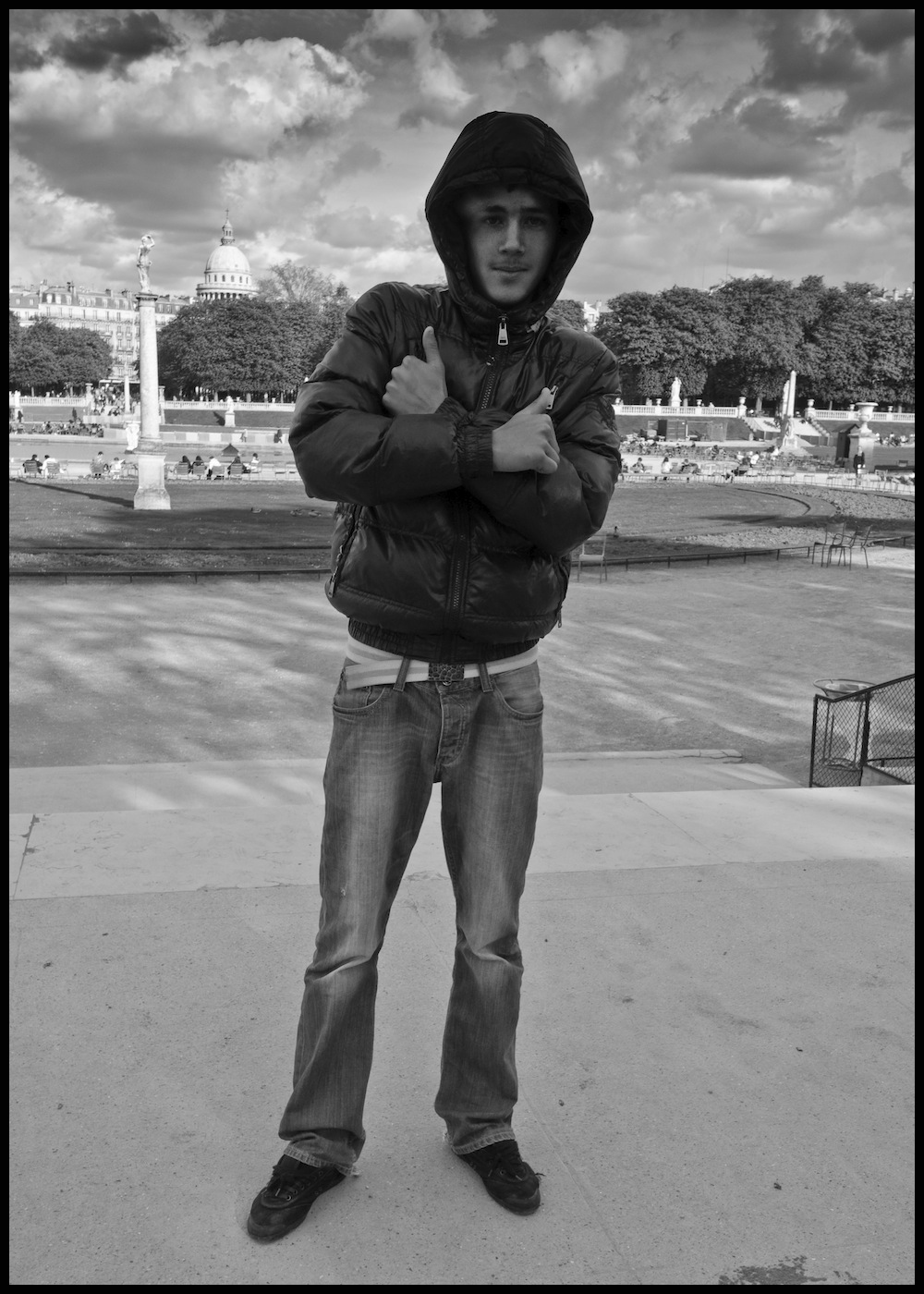

I'm having a cappuccino at a local cafe, and she just walks up and sticks her face in the lens. How could I say no? This kid was the ringleader of the Luxembourg boys seen in color above. They were far too cool to ask for the photos, but the girl they were with asked for them, so I e-mailed copies.

This kid was the ringleader of the Luxembourg boys seen in color above. They were far too cool to ask for the photos, but the girl they were with asked for them, so I e-mailed copies. This guy was the one who asked that I shoot him and his arms-folded buddy in the doorway above. I think they went to arms-folded school together.

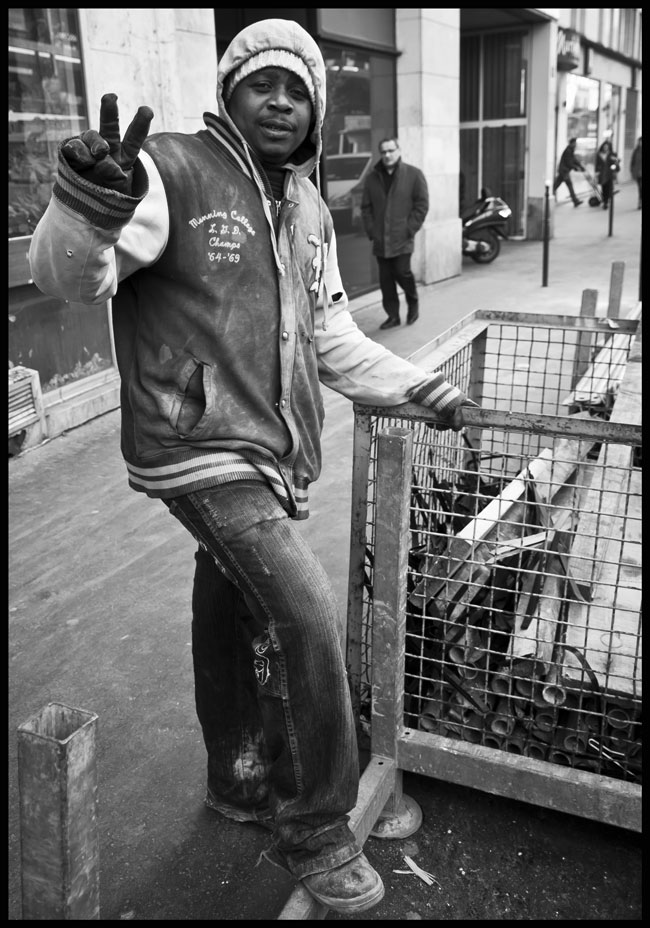

This guy was the one who asked that I shoot him and his arms-folded buddy in the doorway above. I think they went to arms-folded school together. He was saving a parking space for a patron of a neighborhood cafe. Good gig, done with panache.

He was saving a parking space for a patron of a neighborhood cafe. Good gig, done with panache. I was shooting storefronts on the Boulevard Sebastopol, and she waved me over to immortalize her and her companion.

I was shooting storefronts on the Boulevard Sebastopol, and she waved me over to immortalize her and her companion. I thought he was annoyed that I was shooting his construction site, and we didn't have a common spoken language. But then he did this.

I thought he was annoyed that I was shooting his construction site, and we didn't have a common spoken language. But then he did this. She liked her hat; I liked her necklace, which reminded me of street art.

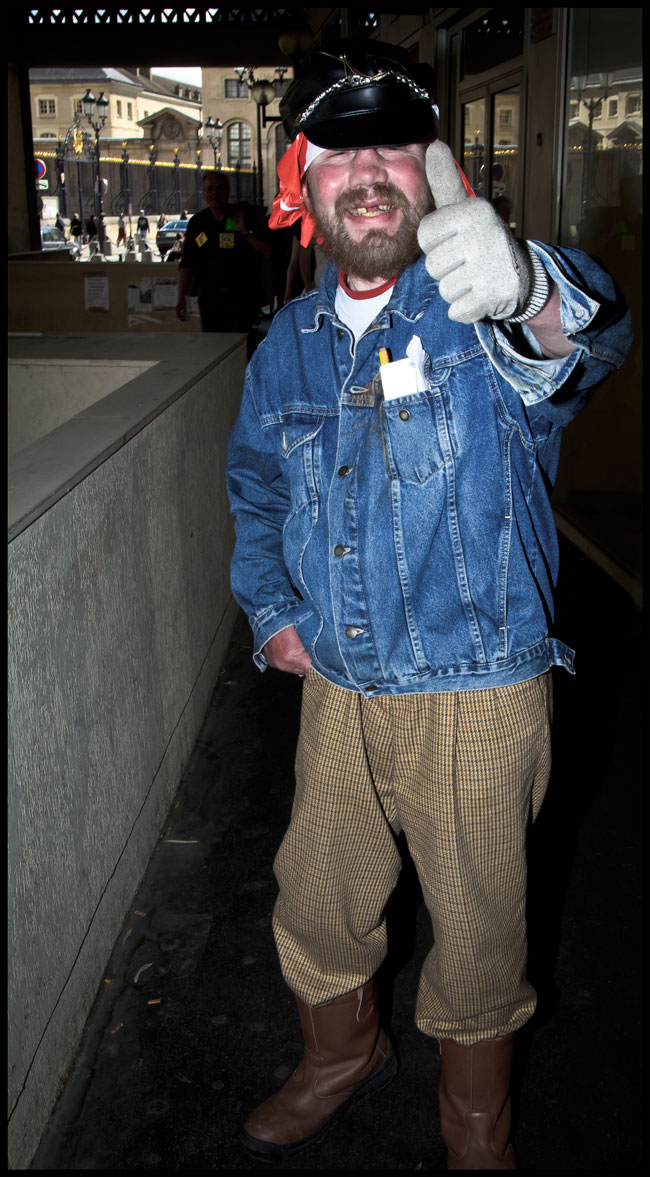

She liked her hat; I liked her necklace, which reminded me of street art. There's a surprising amount of hazing in French schools, during which one is forced to dress up, or down, and be humiliated in public. This guy seems to be making the best of it.

There's a surprising amount of hazing in French schools, during which one is forced to dress up, or down, and be humiliated in public. This guy seems to be making the best of it. Soccer (football, or foot) is the top sport here, but hoop dreams are moving up fast.

Soccer (football, or foot) is the top sport here, but hoop dreams are moving up fast. This is my favorite clochard, who lives under a building overhang on the rue St. Jacques. Always cheerful, a people person.

This is my favorite clochard, who lives under a building overhang on the rue St. Jacques. Always cheerful, a people person. These friends were returning to a worksite that I had just finished shooting.

These friends were returning to a worksite that I had just finished shooting. I was shooting the drama/comedy masks carved into the front of a theater building when she ran up, skinned knees and all, and struck this pose. I shot, and she ran off, giggling, pink backpack bouncing up and down.

I was shooting the drama/comedy masks carved into the front of a theater building when she ran up, skinned knees and all, and struck this pose. I shot, and she ran off, giggling, pink backpack bouncing up and down. Reticence, what's that? I did a sunrise shoot on Montmartre, around 7:30 a.m., and these folks were on their way home from partying all night. But first they had to pose. Later, he mooned me, but that shot is not for our family-friendly publication.

Reticence, what's that? I did a sunrise shoot on Montmartre, around 7:30 a.m., and these folks were on their way home from partying all night. But first they had to pose. Later, he mooned me, but that shot is not for our family-friendly publication.