The Contractor

03.24.2012

03.24.2012

It is good to like your contractor.

We don’t just like our contractor,

we love him.

Loving your contractor—that matters to me.

I come from a family of builders.

In 1950, my father created a construction company in Phoenix, Arizona that is still going strong today.

My fearless brother, Jon, started a green building company a few years ago at the lowest depth of the recession, when the last thing you’d bet on in Phoenix was the success of a fledgling construction company. That is, if you didn’t know Jonny.

The company is flourishing, exploding, really.

Jon and his business partner, Lorenzo, have more jobs than they can handle. The city of Phoenix is so impressed with their community-enhancing projects that they are offering matching funds.

Attitude. Like my father, my brother has the most life-enhancing attitude of just about anyone I know, so magic abounds in his life. You think I’m exaggerating? Try clearing up your ‘tude and watch the magic you attract!

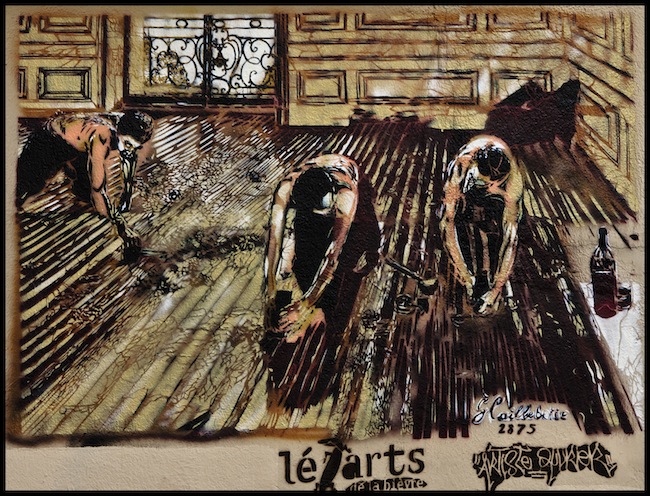

Back to our Paris contractor. Andrew is a quick, tall, slender man of forty, who was raised in South Africa. He came to Paris at the age of 21, and he now speaks the most perfect French of anyone we know whose first language was English.

Andrew did a renovation of our Paris apartment, and has done repairs to it since. His work is impeccable, reasonably priced and finished when he promises to finish.

So who do you think we called to make a few upgrades to our chambre de bonne?

Andrew came by early this week and we sat around our dining room table over coffee and told stories about noisy neighbors. He, like we, lives on the fifth floor of a building, in another arrondissement. (We live in the fifth, the arrondissement of the Book People, the Latin Quarter, where teaching began at the University of Paris, the first in Europe, in the mid-eleventh century.)

A quiet young American woman lived above him. Then she attracted a French boyfriend, Big Foot.

A contractor’s life begins early in the morning and is hard-driving all day. It requires a good night of sleep. The couple upstairs banged around late at night.

Andrew knocked on their door and politely asked for quieter footsteps so late at night. She slammed the door in his face. (And he’s the president of his syndic!)

Another night, they awakened him at 2 a.m. He got out of bed, went upstairs and knocked. No response.

“I know you’re in there,” he called out, “I can hear you. Come to the door, please.”

The boyfriend opened the door and said, “Stop bothering my girlfriend.”

Andrew had no desire to bother the man’s girlfriend, he said, but they were disturbing his sleep!

Who are these people with no empathy, no compassion for others?

We know Andrew. We know his request would have been made in a tactful, reasonable way.

How was it going with our noisy neighbor, Andrew asked.

She’ll be quiet for a few days, so we turn off our white noise fan, and then each succeeding day she’s noisier and noisier.

It’s strange to me, this incapacity some people have to feel others’ reality, this narcissism: Here are my needs. Don’t bother me with yours.

Richard and I walked with Andrew to have a look at our chambre de bonne.

Andrew looked at the place with a contractor’s eyes. “What a mess,” he exclaimed. “What I’d do is knock out this wall and this, and open it into one big room.”

“But we don’t own it,” we said.

He looked around at the red tomettes (floor tiles), which were so old the floor in places rose and fell like the surface of the sea.

He looked at the overhead lights, which were strung on two low-voltage wires all across the ceiling of the kitchen and main room like circular doilies on a clothesline.

He looked at the sink, which had been painted over and was now cracking in spots as if covered with petrified yogurt.

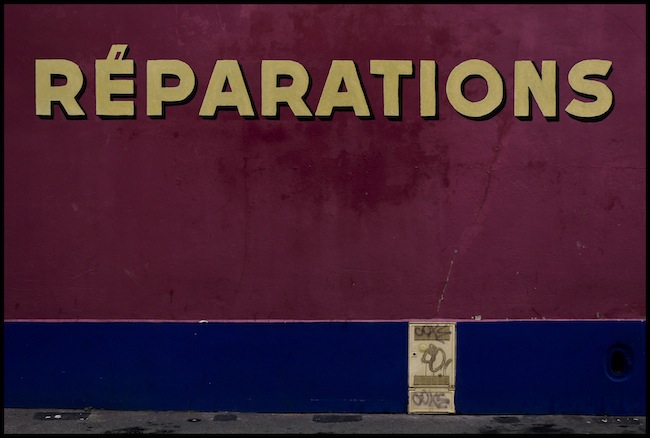

“It does need a few repairs,” I conceded.

Andrew laughed gaily, as if to say, “A few, she says!”

“The landlord is willing to pay to refinish the sink and to fix that baseboard,” Richard said. The baseboard looked as if mice had been gnawing it. There were little holes where it met the floor.

My enchantment with the place had taken a hit. My spirits were sinking.

“It might need painting,” I allowed.

“That’s the least of what it needs,” said Andrew.

We three moved from room to room, making a list of what needed doing: shelves in the bathroom, a couple of missing shelves in the built-in bookshelf, the sink refinished, Ovideu, the whimsical Romanian electrician consulted about whether the ungrounded plugs would still protect my computer if it was plugged into a surge protector.

Andrew said he could spare a carpenter and a painter next week from another job on the Île de la Cité.

We locked the door to our chambre de bonne, waved goodbye to Andrew and headed home.

I was blue the rest of the day. So much of enchantment is subjective. You fall in love with someone or something, and you do not want to hear someone say about your beloved, “What a dog!”

But if the love is true, it lasts.

All night long, half asleep, I envisioned what I’d do to this chambre de bonne: a sisal rug with the right pad beneath would solve the sea-sick-inducing floor. A built-in horseshoe-shaped desk would fit perfectly into the room. The lighting store at the end of our street had a great selection of lights.

I envisioned the stories and poems I’d write, the creative life I’d have in this magical aerie. I began fiddling with the end of a certain short story in my mind.

And then I remembered, This has nothing to do with the surface of the room. It was a matter of atmosphere, of soul. Every writer knows that feeling of walking into a room and thinking, I could write here! It might have something to do with the proportions of the room, it might be the view or the lack thereof, but I think it has more than anything to do with the sense, Here I could work without being interrupted. That is the essential thing that writers need: deep immersion in the dream of the work.

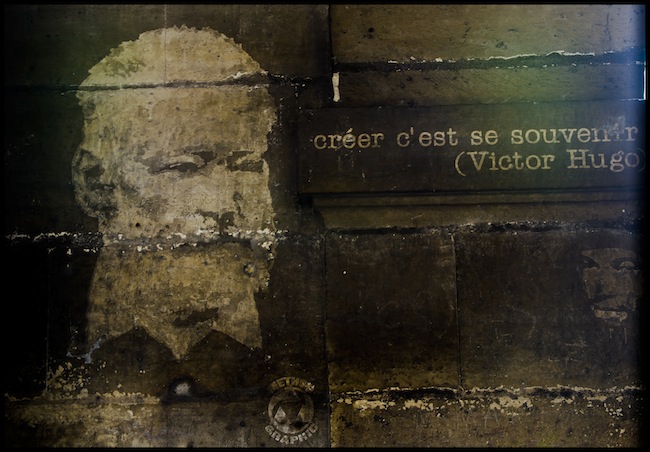

The next morning I asked myself a question: Would Baudelaire have loved this room?

Oh yes he would! I answered.

Then it’s good enough for me. The blues fled, the enchantment returned, and I loved my contractor again.