Genius and Generosity, a (Sort of) Book Review

03.26.2011

03.26.2011

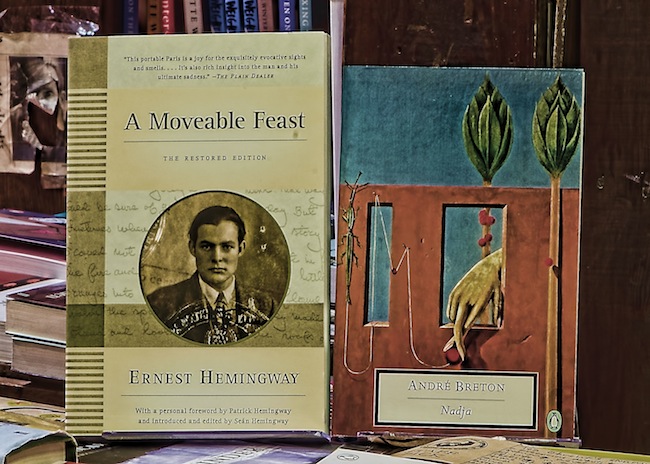

Rereading the restored edition of Ernest Hemingway’s A Moveable Feast has got me thinking about the nature of genius and of love.

This memoir about the American fiction writer’s years in Paris during the twenties is chock full of many of the things I most love: writing, reading literature, Paris, the café life, artistic community, an intimate, supportive marriage.

When Hemingway and his first wife, Hadley, first came to Paris in their early 20s in the early twenties of the twentieth century, they lived on rue du Cardinal Lemoine, just before it opens out onto Place Contrescarpe. Though the name meant little to me when I first read the book in my twenties, now that Richard and I live on rue Cardinal Lemoine, the mention of the street on page two enchants me.

Speaking personally, what more could I ask of a book?

Well, as it turns out, one thing. Rather a big thing. More on that later.

Let’s begin with what is admirable, even breathtaking, about this book. What a model of devotion to the craft of writing Hemingway offers.

Hemingway had just quit his work as a journalist in order to make his way as a writer of fiction. This I admire. In order to find one’s genius one must listen to one’s genius.

Richard and I prefer Plato’s definition of genius in the myth of Er in The Republic to more recent conceptions of genius. Plato tells the story of Er, who, after dying and coming back to life, reveals what he learned: that each of us is born with a genius, a daimon or twin soul, who remembers what our purpose in life is even when we forget, and who is constantly dropping hints to us: not this, not this—yes, that. One’s genius, or purpose could be anything: artist, doctor, builder, business person, homemaker, mother or farmer. But unless we follow what our genius knows we should do in this life, we can’t find fulfillment. Hemingway had the courage to follow his.

Hemingway had impeccable discipline, impressive for a young man in his twenties. He arose early every morning and mounted the steps to the room he rented high in a nearby hotel (the hotel where Verlaine died). The room was so cold that if he left mandarines[1] there overnight, they’d freeze. From the window he could look down and see the goatherd come up the street blowing his pipes and a woman in his building come out onto the sidewalk to buy milk that the goatherd milked as she waited. (Oh, why can’t goats still wander the streets of Paris?)

Courage he had, and discipline. And another thing: luck. He happened to arrive in Paris at a very good time for Americans. The exchange rate was such that a writer, whose advance for a first book of short stories was $200, could, by living frugally (buying no clothes, no paintings, sometimes skipping meals), afford an apartment for himself and Hadley, a hotel room in which to work, and spend winters skiing in Austria, summers at the bullfights in Spain.

What he learned about writing:

“I always worked until I had something done and I always stopped when I knew what was going to happen next. That way I could be sure of going on the next day.”

“I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, “Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence, and then go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence that you knew or had seen or had heard someone say.”

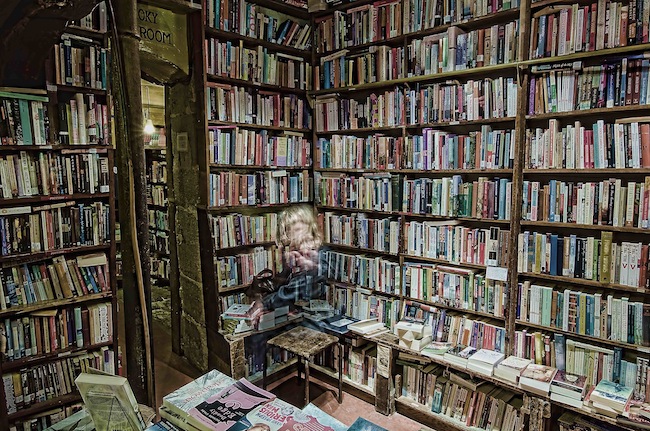

“It was in that room too that I learned not to think about anything that I was writing from the time I stopped writing until I started again the next day. That way my subconscious would be working on it and at the same time I would be listening to other people and noticing everything, I hoped; learning, I hoped; and I would read so that I would not think about my work and make myself impotent to do it.”

And then there were people. Not Hadley. People. He warns us: “The only thing that could spoil a day was people and if you could keep from making engagements, each day had no limits. People were always the limiters of happiness except for the very few that were as good as spring itself.”

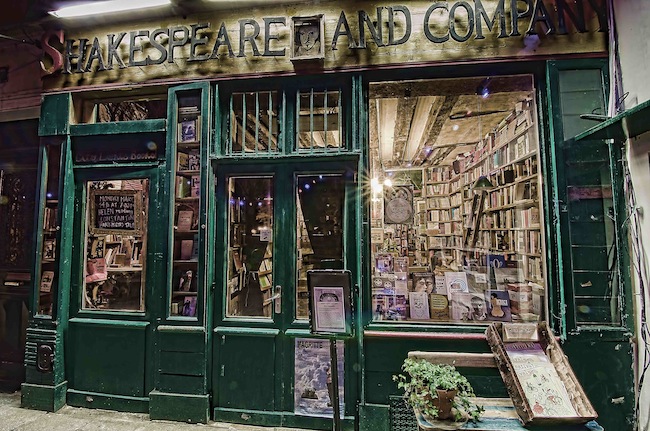

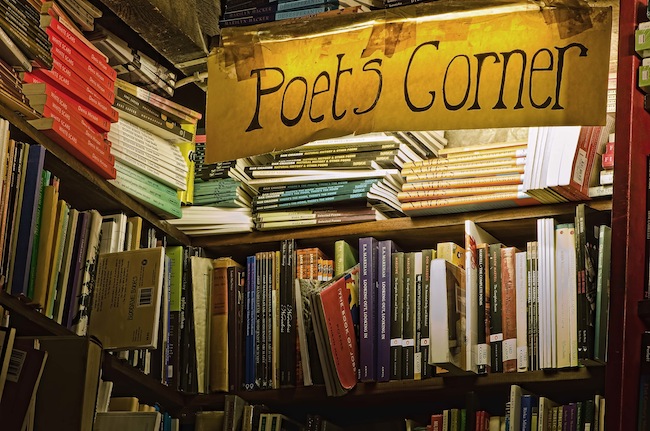

Of course in Hemingway’s world in the Paris of the twenties, “people” meant Gertrude Stein and her companion, Alice B. Toklas; F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda; Ezra Pound; James Joyce; Ford Madox Ford; Wyndham Lewis; Sylvia Beach.

And here is where my enjoyment of the book cools. Hemingway describes Gertrude Stein’s generosity to Hadley and him. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s warmth to him. But his portraits of them are, ultimately, scathing.

From the night he meets Fitzgerald in one of Hem's favorite Montparnasse hangouts, the Dingo Bar, he is sizing him up. From instantly preferring Scott’s friend, the famous Princeton baseball pitcher, Dunc Chaplin, to him; to a head-to-toe physical appraisal: legs too short; wrong kind of tie; a faintly puffy face, to the most damning thing Hemingway can say about a man, that there is something female about him (“a delicate long-lipped Irish mouth that, on a girl, would have been the mouth of a beauty…the mouth worried you until you knew him and then it worried you more”); to how Fitzgerald praised him too much and asked questions that were too direct; to how his face was like a death’s head after a few glasses of champagne. All this in contrast with Hemingway’s portrayal of himself as manly, composed, able to hold his liquor, admirable in most other ways.

Later when Scott invites Hemingway to join him by train to Lyon to pick up a car that Scott and Zelda had had to abandon there because of bad weather, Scott misses the train. Hemingway is unable to reach Scott in Paris, so he goes to the best hotel in Lyon (though he’s worried about spending too much money), where Scott finds him the next morning.

They pick up the Renault at a garage, where the garage man recommends new piston rings, and Hemingway uses the opportunity to display his superior manly knowledge of cars, and Scott’s lack of good sense.

Hemingway notes that Fitzgerald has been drinking when they meet up in the hotel, so Hem suggests stopping in the bar for a whisky and Perrier. They set out on their road trip. Although he’s well aware of how sick alcohol makes Fitzgerald, and that he’s probably an alcoholic, at Macon, Hemingway buys four bottles of excellent wine, which they drink from the bottle as they drive. Another chance to point out how feminine Scott is. “I am not sure Scott had ever drunk wine from a bottle before and it was exciting to him as though he were slumming or as a girl might be excited by going swimming for the first time without a bathing suit.”

By that afternoon, Scott is worried about his health. In the hotel room that night, Hemingway observes Scott’s hypochondria and again dramatizes the slightly older writer’s foolishness to underscore Hemingway’s good sense.

An invitation to Hemingway and Hadley to lunch at Scott and Zelda’s apartment gives Hem the chance to criticize Zelda’s appearance and the meal. And to wonder at Scott and Zelda’s seeming to think that the two men’s road trip from Lyon had been great fun.

In contrast to Gertrude Stein’s generosity to him, Hemingway describes covertly overhearing a lovers’ spat between Gertrude and Alice. “That was the way it finished for me, stupidly enough…”

Having recently read Hemingway’s third wife, Martha Gellhorn’s Selected Letters, this is richly ironic. She describes getting the journalist’s assignment of a lifetime, being one of the only women allowed to cover the European front lines in World War II. Hemingway, at work on a novel at their finca in Cuba, tugs on her to return home, whining about his loneliness until she makes the fatal decision to come home early. He and his drinking buddies have trashed their home, he calls her every vicious name a man can call a woman, then secretly steals her Colliers Magazine assignment and goes off to the front lines himself.

And he’s willing to toss his friendship with Gertrude Stein out the window over one conversation he overheard her have with Alice? Hemingway had four wives. Gertrude Stein and Alice were together till the end. They are now buried side-by-side in Père Lachaise Cemetery, with Gertrude's name on the front of the headstone, Alice's on the back.

I have no idea why Hemingway so hated the English writer Ford Maddox Ford, who apparently was so generous to him.

Or why he savaged the English writer/painter Wyndham Lewis for wearing the “uniform” of a pre-World War I artist, and watching Hem teach Ezra some boxing tricks in a competitive spirit (pot calling the kettle black?). He describes Lewis as having the eyes of a “frustrated rapist.” It’s certainly a memorable phrase.

However, a more treacherous husband or friend I can’t imagine.

Yet, in the descriptions of Hemingway working, or spending winters in Schruns, Austria skiing with Hadley; in short, whenever he’s describing physical life—action, he is magnificent.

It’s when he describes “friends” that I wince. The final portrait of F. Scott Fitzgerald is in a dialogue with Georges, the chasseur[2], later the bar man, at the Ritz Bar, who doesn’t remember Fitzgerald, though the novelist spent many evenings there.

“Papa, who was this Monsieur Fitzgerald that everyone asks me about?.... But why would I not remember him? Was he a good writer?” And “’I remember you and the Baron von Blixen arriving one night—in what year?’ He smiled.”

“He is dead too.”

“Yes. But one does not forget him. You see what I mean?”

Hemingway contrasts how memorable he himself is, and how unforgettable Baron von Blixen, Isak Dinesen’s first husband, was, with how Fitzgerald has simply disappeared from the chasseur’s memory.

Hemingway assures the man that he will do a portrait of Fitzgerald and then the man will remember him. But Hemingway’s portrait has already served its purpose: to demolish Fitzgerald as a man worthy of remembrance or admiration. I suppose one does with one’s friends exactly what one does to oneself. Hemingway killed himself a year after the book was completed in the spring of 1960.

If genius is the pinnacle of human achievement, then Hemingway served his genius well.

But love? Perhaps love is generosity—towards oneself, other people, and life itself. Our parents give birth to us. They care for us (or most do) from birth to adulthood, and sometimes beyond. We are alive on this beautiful earth, surrounded by mysterious objects, people, adventures, the sweetness of love and the challenge of work. Shouldn’t we return the favor with generosity towards life in all its many forms?

If generosity—love, really—is the pinnacle of human relationship, Hemingway was a sad specimen of humanity.

[1] mandarin oranges

[2] a hotel employee who takes care of outgoing mail, and retrieving theater tickets.

Hemingway,

Hemingway,  Paris,

Paris,  Stein,

Stein,  memoir in

memoir in  Paris Life

Paris Life