Wedding in Elounda Beach, Crete

08.3.2011

08.3.2011

This weekend we attended the three-day wedding celebration of two friends in the Loire Valley. Marriage ceremony in an eleventh century church, reception at a restored chateau, two parties at family homes. More on that in a later Paris Play, but it set us thinking about weddings. Here's how we were married three times in Elounda Beach, Crete:

Holed up in the Mirabello Bay hotel

the night before our wedding, we ask the gods,

What shall we do for our wedding vows?

When you summon them, how swiftly they speak!

We wake at three a.m., envision

a circle of gods and goddesses around us,

twelve of them, played by our guests

speaking our vows, which we will repeat.

We run to Ayios Nikolaos, find playing cards

with images of the twelve, dash home to write

and paste the words of the vows over the numbers,

diamonds, clubs, spades and hearts.

Crete is the shape of a woman with bare breasts,

belled dress—Ariadne, the Cretan Aphrodite.

We gather in the crook of her neck at the Elounda Beach hotel

at the edge of the Aegean sea.

My parents’ wedding gift: five days in white casitas

with curved walls, woven Greek bedspreads,

rooms open to sapphire water, June sky,

a horseshoe of mountains beyond.

Father, mother, sister, brother, sister, sister.

two nieces, and brother's fiancée.

Married friends of 30 years, their daughter.

Twelve guests are here.

Sister Ann brings the boxes with wedding rings

we’d given them to take from Arizona.

“We lost the gold ones,” she says,

“so we replaced them.”

I open the box. A smaller ring

with a yellow plastic duck, a larger one

with a red and black ladybug,

both lucky charms. We slip them on.

An hour before the ceremony

I sit with arms and feet outstretched

in white lace nightgown, with

lovely young attendants, nieces

who paint my nails, give me

my first pedicure. I feel like a queen.

“Now I must dress,” I say like a queen.

They laugh, “Isn’t this your wedding dress?”

My father comes to the casita, in striped peppermint shirt,

walks me to the chapel. My sandals are delicate,

earth-gold, worthy of Aphrodite, and hurt my feet.

I think of Yeats’s line about women, “we must labour to be beautiful.”

Through purple bougainvillea, shimmering heat,

we walk the path. My father says, “This man

is a treasure, a jewel. Treat him like one.”

I will, Dad. I will.

My father and I stop across the Dionysus courtyard

from Richard. He stands with radiant face

outside the east door of the chapel,

as Greek grooms do.

The hotel pianist noodles romantic tunes.

My father’s face is shining.

We wait. And wait. My brother snaps photos.

Two men dash across the grounds,

one with patriarchal beard and long black robe,

the other in the last madras shirt in the Western world.

Richard consults with them.

The hotel manager translates.

“What is your religion?” asks the priest,

“Catholic or Orthodox?”

“Neither,” says the groom; “we honor

the ancient Greek gods and goddesses.”

Father Ted looks confused.

The manager tries to translate.

“Which of the two are you?” he insists.

Again Richard states our beliefs.

Father Ted slaps his forehead.

“Pagans!” he cries. And then,

“I can’t take money for this—

it won’t be a real wedding.”

“That’s okay,” says Richard.

“We were already married legally at city hall.

We simply sought the blessing of a local holy man.”

The good priest grudgingly agrees.

The piano man begins the wedding march.

My father escorts me into the Orthodox chapel.

Saints and angels and whirling circles

are painted along the walls.

My mother wears shell-pink linen,

and a necklace of many-colored beads.

Her face is tender and open. My father

places my hand in my beloved’s.

We tremble before the sermon

Father Ted bellows in Greek.

His madras-shirted cantor translates:

“You were born in sin, and will burn in hell!”

Is this a special Bible treat

especially for pagans? We float out of the chapel

amazed, shocked by the spiritual violence,

gather in the Dionysus courtyard.

“Where did you find this jacket?” asks Suki,

stroking my sleeve. It is white silk ribbon with a labyrinth

design. “On Mykonos,” I say, remembering

my joy at finding it in the maze of shops.

“The bride talks too much,”

the hotel manager says.

A proper Greek bride

should be Orthodox and silent.

We walk to the stone jetty

that juts out into the Aegean sea.

It ends in a circle with canvas wicker chairs,

several hotel guests at the open bar.

A white sail forms a roof,

open to cobalt sea and sky,

and mountains like Arizona beyond.

Our guests form a circle around us.

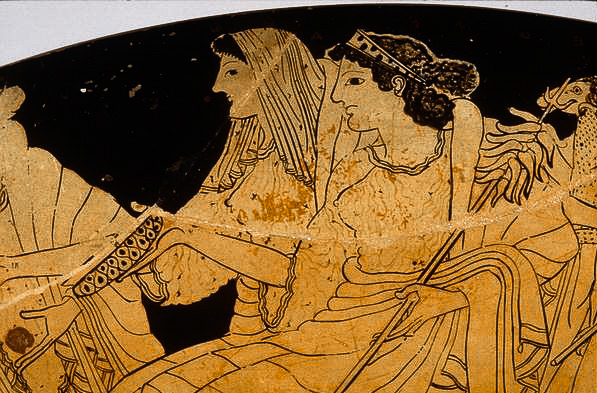

The gods of water, Poseidon, Dionysus and Artemis to the North;

the gods of air, Hermes, Daedalus and Athena to the East;

the gods of earth, Hestia, Aphrodite and Demeter to the South;

the gods of fire, Ares, Apollo and Zeus to the West.

My mother, Betty, Artemis, opens her envelope, and reads:

I will protect and nurture you.

My niece, Bayu, as Hermes, is next:

I will strive to deeply understand you.

After each, we echo the vows.

My brother, Jon, as Daedalus, says,

I will guard your creative solitude.

The gods and goddesses weep.

Jon’s fiancée, Leatrice, Athena, says,

All my resources are yours.

I will build a home with you, says Steve,

representing Hestia.

Aphrodite speaks through his daughter, Robin,

I will walk in beauty with you.

Her mother, Rain, is Demeter:

I will nourish you and protect your health.

I will travel the world with you, says Ares sister, Ann.

Sister Suki, Apollo, says, I will live with you in harmony

and celebration. Sister Jane, as Zeus says:

I will be grateful every day for the gift of you.

Her daughter, Rachel, Poseidon, says,

I will protect your sleep and honor your dreams.

My father, Sam, as Dionysus, ends with:

You are the mate of my soul in life and in death.

Everyone cries except my mother, Artemis,

who dry-eyed says, “This should be a film.”

A young Greek woman approaches from the bar, asks,

“What is this beautiful religion?” “Yours,” we say.

We sit on the banquettes,

gazing around at the mountains and sea.

This is where we wanted to be married,

Ariadne’s island of beauty and love.

We walk in a procession to the Dionysus courtyard

for the feast. Long white-clothed tables form a T.

Red roses in glass vases. A menu of

Aphrodite’s Appetizers. Fillet of Fresh Fish Poseidon.

Lemon Sorbet Artemis. Rack of Lamb Ares.

Fresh Fruit from Demetra’s garden.

Hestia’s homemade chocolate cake.

Coffee a la Hermes. Dionyssos’s digestives.

The air is warm. We sit under the umbrellas of olive trees.

The sculpted white chapel where we were hectored

in sin is behind us. We sit with family and friends,

ablaze with love.